to

TOP

With OpEx and CI, a multitude of disciplines and methodologies can be applied. Each framework or discipline has its own focus on how to gather information and analyze it properly to enable improvement. The real trick is in figuring out which methodology or tool to bring to bear against a given problem.

Kaizen: Focus on Individual Incremental Process Improvement

The Japanese word "Kaizen" simply means "good change" or "change for better." While Kaizen is touted as a Japanese concept or philosophy and as a business concept has gained noteriety over the years by being used to label improvements within the practices and techniques spearheaded by Toyota, Kaizen in reality is a technique applied by almost all people in everyday use.

The concept refers to any improvement -- single or continuous, large or small -- and is evidently embedded in human DNA. Examples of everyday people employing the Kaizen concept are all around us every day:

- Finding a better route to or from work, or changing what time we go and return, to avoid the delays of rush-hour traffic.

- Changing how or when we purchase groceries so we can take advantage of cost savings opportunities.

- Improving our relationships with our friends so that we can enjoy more weekend activities that make us happy.

- Changing our dietary habits so we can loose a few pounds and improve our health.

I think you can see how each of these could be a "good change" or "change for better" which qualifies under the definition of Kaizen.

The business discussion of the Kaizen concept generally focuses on two approaches:

- Personal Kaizen improvements - typically workflow improvements made by individual workers within their immediate sphere of influence. A simple "I/we can do this better if I/we just change this..." and making the change immediately without fanfare or excessive planning needed.

- A Kaizen Event or Kaizen Blitz - typically structured as a team event to solve a problem and create a quick solution for improvement. Usually this takes the form of a series of workshops performed within a short time frame to a) outline and understand the problem, b) brainstorm and profer solutions, c) design a quick experiment to test the chosen solution, d) evaluate the success and subsequently adopt the change system wide.

In many organizations, Kaizen is promoted as a daily activity to drive operational teams beyond simple productivity improvements. When done correctly it empowers people to become problem solvers and how to perform experiments on their own work. Successfully implementing the Kaizen concept within a business can ultimately lead to higher customer satisfaction, lower cost, and more satisfied employees.

While Kaizen may deliver a host of small improvements, and while many of the improvements may not be identified directly with these benefts, the continuous alignment and standardization can yield large exponentially impactful results. People at all levels of the organization should participate in the Kaizen culture, from the CEO down to janitorial staff. There can be huge benefit by exposing external stakeholders to the concept as well.

Lean: Focus on Removing Waste

"Lean" as a discipline (as opposed to Six Sigma) is a focus on principles developed and proven by the Japanese manufacturing industry. The term Lean was coined by John Krafcik (MBA from MIT, and former Qality Engineer at the Toyota-GM NUMMI joint venture) in his 1988 article, "Triumph of the Lean Production System." Krafcik's research, continued by the International Motor Vehicle Program (IMVP) at MIT was instrumental in the book "The Machine That Changed the World," co-authored by James P. Womack and Daniel Jones.

The focus of Lean is the continuous identification and elimination of waste, often divided into the eight categories shown in the graphic to the right. Every process can be broken down into steps or components, and the value of each discrete part can be classified as "value add" (VA), "non-value add" (NVA) and "necessary, but non-value add" (NNVA). Non-value add elements within the process can further be subdivided into three types outlined as "muda" (non-value-adding work), "muri" (overburden), and "mura" (unevenness).

Theoretically, as waste is eliminated quality improves, production time is decreased, and cost is reduced. "The Toyota Way" (Lean as presented within Toyota Manufacturing) focuses on improving the "flow" or smoothness of work, thereby steadily eliminating unevenness through the system. This is accomplished through use of techniques and tools such as production leveling, "pull" production (minimization of inventories) and the Heijunka box - a visual scheduling tool allowing easy and visual control of a smothed production schedule.

Ideally the techniques of Lean are used to expose problems systematically and to use the Lean tools to reduce waste where the ideal cannot be achieved. Lean implementation emphasizes the importance of optimizing work flow through strategic operational procedures while minimizing waste and being adaptable. Flexibility is required. All of the findings of Lean analysis must be acknowledged by employees who develop the products and initiate processes that deliver value. The cultural and managerial aspects of Lean are arguably more important than the actual tools or methodologies of production itself. There are many examples of Lean tool implementation without sustained benefit, and these are often blamed on weak understanding of Lean throughout the whole organization.

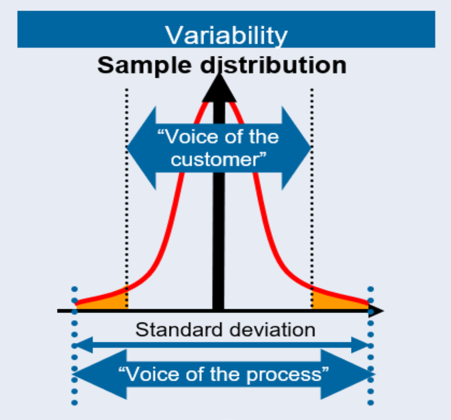

Six Sigma: Focus on Removing Variability

Six Sigma is a set of techniques and tools for improving the reliability of processes. It was introduced by engineer Bill Smith while working at Motorola in 1986, and was proliferated throughout the General Electric corporate culture by Jack Welch, who made it a big part of business strategy at GE in 1995.

It seeks to reduce the number of defects produced by a process (variability) and improve reliability of the process (standardization). This will improve the quality of the output to customers. It uses a set of tools and methods for analyzing current systems, implementing change, and maintaining the improvements through monitor and control. These tools and analytics are largely statistical in nature.

Some organizations and practitioners combine Six Sigma ideas with Lean ideas to create a practice called Lean Six Sigma. Combining these two views can effectively address process flow and waste issues with the added rigor and statistical nature of Six Sigma. The benefit of this combined focus as complementary disciplines is largely the thinking that has promoted "business and operational excellence". Lean Six Sigma can focus transformation efforts not just on efficiency but also on growth. It serves as a foundation for innovation throughout the organization, from manufacturing and software development to sales and service delivery functions.

Organizations who subscribe to Six Sigma ideology create a special infrastructure of people within the organization who are experts in these methods. These people trained in Six Sigma methodology are generally divided into tiers, each with a certain sphere of influence over the application of the Six Sigma program:

Typical Six Sigma Hierarchical Structure

| | Role | Scope | Work |

|---|

| | White Belt | all employees | Six Sigma aware |

| | Yellow Belt | most operations employees | participate passively in projects |

| | Green Belt | most leaders | participate actively in projects |

| | Black Belt | project mgrs | manage transformational projects |

| | Master Black Belt | program manager | manage the Six Sigma program |

Each Six Sigma project carried out within an organization follows five step sequences inspired by Dr. W. Edwards Deming's Plan-Do-Check-Act Cycle and must have specific demonstrable targets, such as reduction in cycle time, reduction in materials cost, reduction in labor cost, measureable increases in quality and customer satisfaction, or measureable increases in profits.

There are two defined sequences composed of five phases:

- DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) is used for projects aimed at improving an existing business process

- DMADV (Define, Measure Analyze, Design, Verify) is used for projects aimed at creating new product or process designs

The term Six Sigma comes from statistical modeling. The process can be described by a sigma rating indicating its final yield or the percentage of defect-free products it creates. A six sigma process is one in which the process produces no more than 3.4 defective features per million opportunities (99.99966% expected to be free of defects).

Six Sigma doctrine asserts:

- Continuous efforts to achieve stable and predictable process results (e.g. by reducing process variation) are of vital importance to business success.

- Manufacturing and business processes have characteristics that can be defined, measured, analyzed, improved, and controlled.

- Achieving sustained quality improvement requires commitment from the entire organization, particularly from top-level management.

For Six Sigma to be successful and sustainable in an organization there must be an increased emphasis on strong and passionate management leadership and support. This must include a clear commitment to making decisions on the basis of verifiable data and statistical methods, rather than assumptions and guesswork.

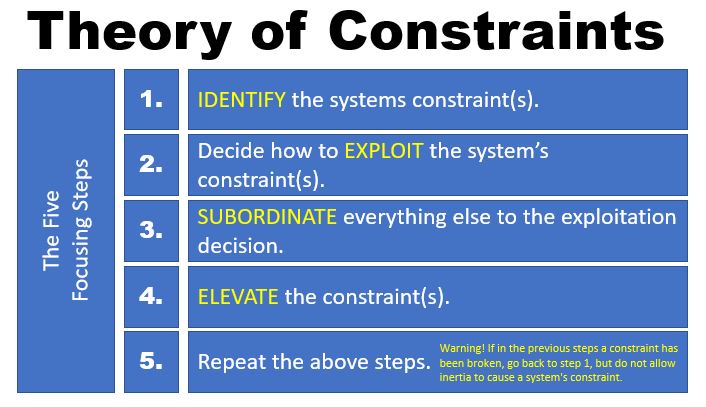

Theory of Constraints: Focus on Removing Bottlenecks

To quote a line from a famous game show... "You ARE the weakest link!"

Theory of Constraints (ToC) is a methodology that views any manageable system as being limited in achieving more of its intended purpose by constraints within the system. There is always at least one constraint, and processes or organizations are vulnerable because the weakest person or part can always damage or break the system, or at least adversely affect the outcome.

ToC uses a set of "focusing steps" to identify the constraint and restructure the rest of the system around it. Organizations can be measured and controlled by variations on three measures: throughput, operational expense, and inventory. Inventory is all the money that the system has invested in purchasing things which it intends to sell. Operational expense is all the money the system spends in order to turn inventory into product. Throughput is the rate at which the system generates money through sales.

Only by increasing flow through the constraint can overall throughput be increased. There is an argument to be considered when practicing Theory of Constraints: "Reductio ad Absurdum." This concept is as follows: If there was nothing preventing a system from achieving higher throughput, its throughput would be infinite. Obviously, this is impossible in a real-life system.

The five focusing steps of ToC aim to ensure ongoing improvement efforts are centered on the organization's constraints. In the ToC literature, this is referred to as the process of ongoing improvement (POOGI).

Project Management: the PMI & PMBOK - Rigorous PM Framework and LifeCycle

Foundational Standards

The standards promoted by the Project Management Institute provide a foundation for project management knowledge and represent the four areas of the profession: project, program, portfolio and the organizational approach to project management. They are the foundation on which practice standards and industry-specific extensions are built.

The PMI Standards are established by consensus, documented and approved by a recognized body, which provides for common and repeated use, rules, guidelines or characteristics for activities or their results, aimed at the achievement of the optimum degree of order in a given context. Developed under a process based on the concepts of consensus, openness, due process, and balance, PMI standards provide guidelines for achieving specific project, program and portfolio management results.

Project Management Professional (PMP)®

The Project Management Professional (PMP)® is the most important industry-recognized certification for project managers. You can find PMPs leading projects in nearly every country and, unlike other certifications that focus on a particular geography or domain, the PMP® is truly global. A PMP can work in virtually any industry, with any methodology and in any location.

The PMP Certification signifies that you speak and understand the global language of project management and connects you to a community of professionals, organizations and experts worldwide.

The PMP can also provide a significant advantage when it comes to project success. When project managers are PMP-certified, organizations complete more of their projects on time, on budget and meeting original goals. (Pulse of the Profession® study, PMI, 2015.)

Ethics in Project Management

Responsibility. Respect. Fairness. Honesty. These are the core values of the PMI Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct. All of our members, volunteers and certification holders must comply with code and uphold its values.

Project Management FRAMEWORK and CHECKLIST:

Agile & Scrum: Focus on Fast-Moving and Iterative Project Management

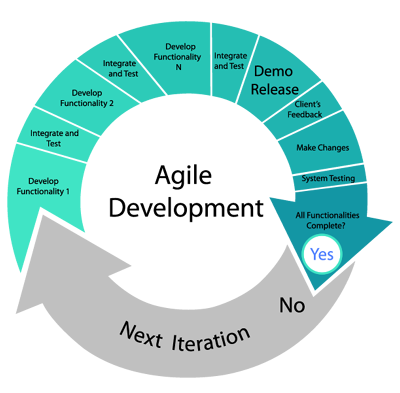

Agile project management describes an approach often used for software development or product development, under which requirements and solutions evolve through the collaborative effort of self-organizing and cross-functional teams and their customers/end users. It advocates adaptive planning, evolutionary development, early delivery, and continual improvement, and it encourages rapid and flexible response to change.

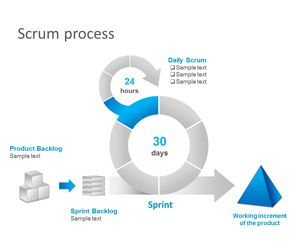

Most agile development methods break product development work into small increments that minimize the amount of up-front planning and design. These work increments are tackled in multiple iterations, or sprints, with short time frames (timeboxes) that typically last from one to four weeks.

Each iteration involves a cross-functional team working in all functions: planning, analysis, design, coding, unit testing, and acceptance testing. At the end of the iteration a working product is demonstrated to stakeholders. This minimizes overall risk and allows the product to adapt to changes quickly. An iteration might not add enough functionality to warrant a market release, but the goal is to have an available release with minimal bugs at the end of each iteration. Multiple iterations might be required to release a product or new feature. Working software is the primary measure of progress.

The term Agile was popularized in this context by the "Manifesto for Agile Software Development." The values and principles espoused in this manifesto were derived from a broad range of software development frameworks including Scrum and Kanban.

The Manifesto for Agile Software Development

Agile software development values

In 2001, seventeen software developers met at a resort in Snowbird, Utah to discuss these lightweight development methods, among others Jeff Sutherland, Ken Schwaber, Jim Highsmith, Alistair Cockburn, and Bob Martin. Together they published the Manifesto for Agile Software Development.

Based on their combined experience of developing software and helping others do that, the seventeen signatories to the manifesto proclaimed that they value:

- Individuals and Interactions over processes and tools

Tools and processes are important, but it is more important to have competent people working together effectively.

- Working Software over comprehensive documentation

Good documentation is useful in helping people to understand how the software is built and how to use it, but the main point of development is to create software, not documentation.

- Customer Collaboration over contract negotiation

A contract is important but is no substitute for working closely with customers to discover what they need.

- Responding to Change over following a plan

A project plan is important, but it must not be too rigid to accommodate changes in technology or the environment, stakeholders' priorities, and people's understanding of the problem and its solution.

That is, while there is value in the items on the right, they value the items on the left more.

Some of the authors formed the Agile Alliance, a non-profit organization that promotes software development according to the manifesto's values and principles. Introducing the manifesto on behalf of the Agile Alliance, Jim Highsmith said:

"The Agile movement is not anti-methodology, in fact many of us want to restore credibility to the word methodology. We want to restore a balance. We embrace modeling, but not in order to file some diagram in a dusty corporate repository. We embrace documentation, but not hundreds of pages of never-maintained and rarely-used tomes. We plan, but recognize the limits of planning in a turbulent environment. Those who would brand proponents of XP or SCRUM or any of the other Agile Methodologies as 'hackers' are ignorant of both the methodologies and the original definition of the term hacker."

— Jim Highsmith

Agile software development principles

The Manifesto for Agile Software Development is based on twelve principles:

- Customer satisfaction by early and continuous delivery of valuable software

- Welcome changing requirements, even in late development

- Working software is delivered frequently (weeks rather than months)

- Close, daily cooperation between business people and developers

- Projects are built around motivated individuals, who should be trusted

- Face-to-face conversation is the best form of communication (co-location)

- Working software is the primary measure of progress

- Sustainable development, able to maintain a constant pace

- Continuous attention to technical excellence and good design

- Simplicity—the art of maximizing the amount of work not done—is essential

- Best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams

- Regularly, the team reflects on how to become more effective, and adjusts accordingly

© 2017, 2018 Douglas C. Jackman - Webmaster